|

| Obituary, The Good Templar |

A few weeks ago, in the Scottish Indexes online conference Q&A session, a viewer asked about sourcing records for the temperance organisation, the Good Templars.

I was surprised, but

happy to answer the question, because some years ago, I researched a family whose father

was a member of this Victorian order. Plenty of information about the family, the Wyatts, had been forthcoming from the usual BMD and

census records, and more was to be discovered in Post Office directories, electoral rolls, journals, and newspapers - all from the starting point of the newspaper announcement where I came across the Good Templars for the first time:

|

| Glasgow Herald, 27 November 1899 |

Not having realised that Henry was part of something bigger, I researched the Good Templar organisation at Glasgow's Mitchell Library and found that they held a run of Good Templar journals. Here I was astonished to see the picture of Henry (at the head of this article) staring back at me from his obituary.

Born in the parish

of Holborn, London around 1824, according to census returns –

although the church records of the parish haven’t yet yielded up

any proof of this – Henry Wyatt arrived in Glasgow in the late

1840s. He and his wife, Sarah Ann Reynolds, had seven children, all

born in Glasgow between 1847 and 1858: Joseph, Benjamin, Mary Jane,

Elizabeth, Emily, Sarah Ann, and Margaret. The family seemed to be

attached to the Episcopal Church in the heart of the city, St Andrews

by the Green, where four of their first five babies were christened. The one

exception, Elizabeth, was taken to Christ Church in Bridgeton, an East end Episcopal church, for her baptism, while the next child,

Emily, was brought to St Andrews to be christened. Whether this back-and-forth was due to the usual church being temporarily out of commission, a relative’s choice,

or a preference for a specific clergyman, is still not clear.

In 1855, Henry’s

father Benjamin travelled to Glasgow from England. Widowed when Henry

was a boy, Benjamin had remarried in 1831 in Liverpool, and it was

there that his second wife had died in the summer of 1854. It’s

unclear whether he planned to remain in Glasgow with Henry, because a month after his arrival, he died after suffering from gastritis for eight weeks. This would have been a devastating blow to

his family as he was only 54 years old; however, the date of his

demise was a big genealogy plus, as this was the year in which civil

registration had been introduced in Scotland. For just 1855, extra

details were included in birth, marriage, and death records, meaning

that a lot of information was gleaned about the Wyatt family.

Henry registered

his father’s death, and the certificate recorded all of the following: Benjamin had been born around 1802 in London and had been married twice.

His first wife was Henry’s mother, Mary Soliman, and together they

had four children: Caroline, born about 1820, Susanna, who died in

1822 aged 1, Emma, born 1824, and Henry. Benjamin’s second wife was

Frances Higham (their marriage produced no children according to the

certificate) and his parents were named as Edward Wyatt, a

lamplighter, and Susan, whose maiden surname was unknown. This proved a great foundation on which to build the structure of the family, chasing up and trying to confirm (or otherwise!) all these details.

It later came to light that Caroline also moved to Glasgow, was married, and lived to the splendid old age of 96.

Henry continued to

earn a living by various means, as indicated in the census. His

occupation was listed as, from 1851, a clothes broker and a general

dealer, and by 1871 he had become a hotel keeper. This may have been

precipitated by his sequestration that March, as recorded in the

Edinburgh Gazette: “The

Estates of Wyatt &

Company, Furnishing

Warehousemen in Glasgow, and

Henry Wyatt, Furnishing

Warehouseman

in Glasgow, the sole Individual

Partner

thereof, as such Partner,

and as an Individual,

were sequestrated on the 3d

day of March 1871, by the Sheriff of Lanarkshire." How

he managed to get back on his feet in such impressive style, I was never able to discover!

Among

all this wheeling and dealing, in 1867 Sarah Ann died at the

relatively (even for those days) early age of 41. The cause of death

on her burial record is noted as “Debility”, an unsatisfyingly

vague description. Four months later, Henry married Mary Mitchell,

seventeen years his junior and the daughter of Irish immigrants.

Records don’t show them having any further children, but Mary would

have had her hands full anyway,

with all five girls still

living at home, ranging in

ages from 9 to 16.

In the 1871 census

Henry’s home address was given as 63 Candleriggs, and this was also the

location of one of his hotels. As can be seen in the advert below, he was by

now involved with the Good Templars and operated his establishment as

a temperance hotel.

This was an idea begun by the abstention campaigner Joseph Livesey in

the 1830s. It was intended to provide a "dry" alternative to the

ubiquitous availability of alcohol in lodging-houses and inns, in an

effort to check the spread of drink-related social issues in

Britain.

|

| Post Office Directory advert, 1875 |

The temperance

movement used a variety of methods to appeal to people and convince

them of the evils of “the demon drink”, and Henry seemed to be

deeply committed to this cause. He had become a member of its

“Scotland’s First” lodge soon after it was set up in Glasgow,

in August of 1869, at a meeting of the United Working Men’s Total

Abstinence Society.

Its fraternal nature was similar to that of the Freemasons and other

groups who claimed good works as their main focus, although the Templars also admitted female members.

Henry’s daughter

Sarah Ann was recorded as working as an assistant manager in the

Candleriggs location. The Wyatt temperance hotels expanded to include

two more in Glasgow, in nearby Brunswick Street and in Dundas Street, and

eventually one in the Ayrshire coast town of Prestwick.

His obituary

outlined the work Henry carried out in support of the temperance movement: “For

many years he was a fearless champion of the cause. He conducted

Temperance meetings on [Glasgow] Green with much acceptance. His

genial, happy manner carried conviction, and led many to sign the

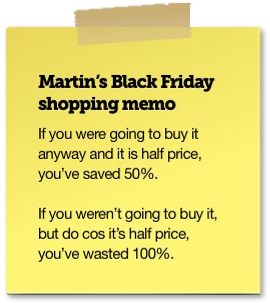

pledge.” This referred to the abstinence pledge that temperance workers encouraged everyone to take, swearing off alcohol for life.

|

| 19th century Canadian Good Templar Pledge |

Things appeared to be going well for Henry in the 1880s, but this wasn't to last. Further bankruptcy proceedings were initiated in 1887, with Henry being described as a "hotel proprietor dealer in furniture". He clearly enjoyed having more than one string to his bow, but perhaps this caused him to overextend financially. A few years later he was still operating the hotels in Brunswick Street and Dundas Street, as well as a restaurant next door to the latter.

By the end of the

decade he had relocated himself, wife, and business to Prestwick. He

transferred his Good Templar membership to the local “St Nicholas”

lodge and continued his association with the temperance cause.

Unfortunately financial ruin continued to dog his footsteps, and an

article in the Glasgow Herald

in November of 1897 reported Henry’s detailed account of his hotel

businesses and family assets.

He was 73 by this time and not in good health, being

unable to read handwriting (as opposed to printed matter) and

therefore his bookkeeper’s ledgers.

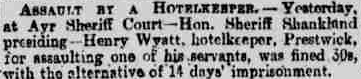

The strain of this

had possibly led to this blot on his copybook, just a

few months previously:

I would hope that he was able to take the fine option...

On the 24 November

1899, Henry died at his home, South Lodge in Prestwick, of dropsy –

a term used to describe the symptoms of what was often heart

failure.

His obituary referred to his “lengthened illness”.

Henry was buried in

Glasgow, in the Southern Necropolis, and his funeral was conducted by

his fellow Templars. It was this obituary, published in the Good Templar journal, that allowed me to learn about his service in the temperance movement, so I suggested these journals to the researcher who was looking for records. I neglected to tell her that the Templars' Scottish records are held at Glasgow University Archives - perhaps I should take my own advice and visit them to learn even more about Henry!